HEART UK’s consensus statement recommends

that serum Lp(a) levels be measured in five

specific population groups:1

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), or other genetic dyslipidaemias

A personal or family history of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), less than 60 years of age

First degree relatives with raised serum Lp(a) levels (>200 nmol/L)

Calcific aortic valve stenosis (CAVS)

A borderline increased (but <15%) 10-year risk of a cardiovascular (CV) event

Identifying Lp(a) disorder and those at risk has been difficult due to inconsistent lab units and lack of standardised recording. To improve documentation and identification of those with elevated Lp(a) or those who are at risk of the condition, SNOMED CT codes have been developed:18

1264212004 – Lipoprotein (a) hyperlipoproteinaemia (disorder)

1264214003 – Family history of lipoprotein (a)

hyperlipoproteinaemia (situation)

It is well-established that Lp(a) levels and their distribution vary with ethnicity and local population structures.1 Black populations have the highest Lp(a) levels of all ethnicities followed by South Asians, Whites, Hispanics, and East Asians.2

Ethnic differences in Lp(a) level and distribution can be partly explained by differences in apo(a) size, which is coded for by the LPA gene, and genetic polymorphisms within and surrounding the LPA gene locus. Elevated Lp(a) levels are associated with CV disease risk in all ethnic groups, but some ethnic groups may require different risk thresholds.2

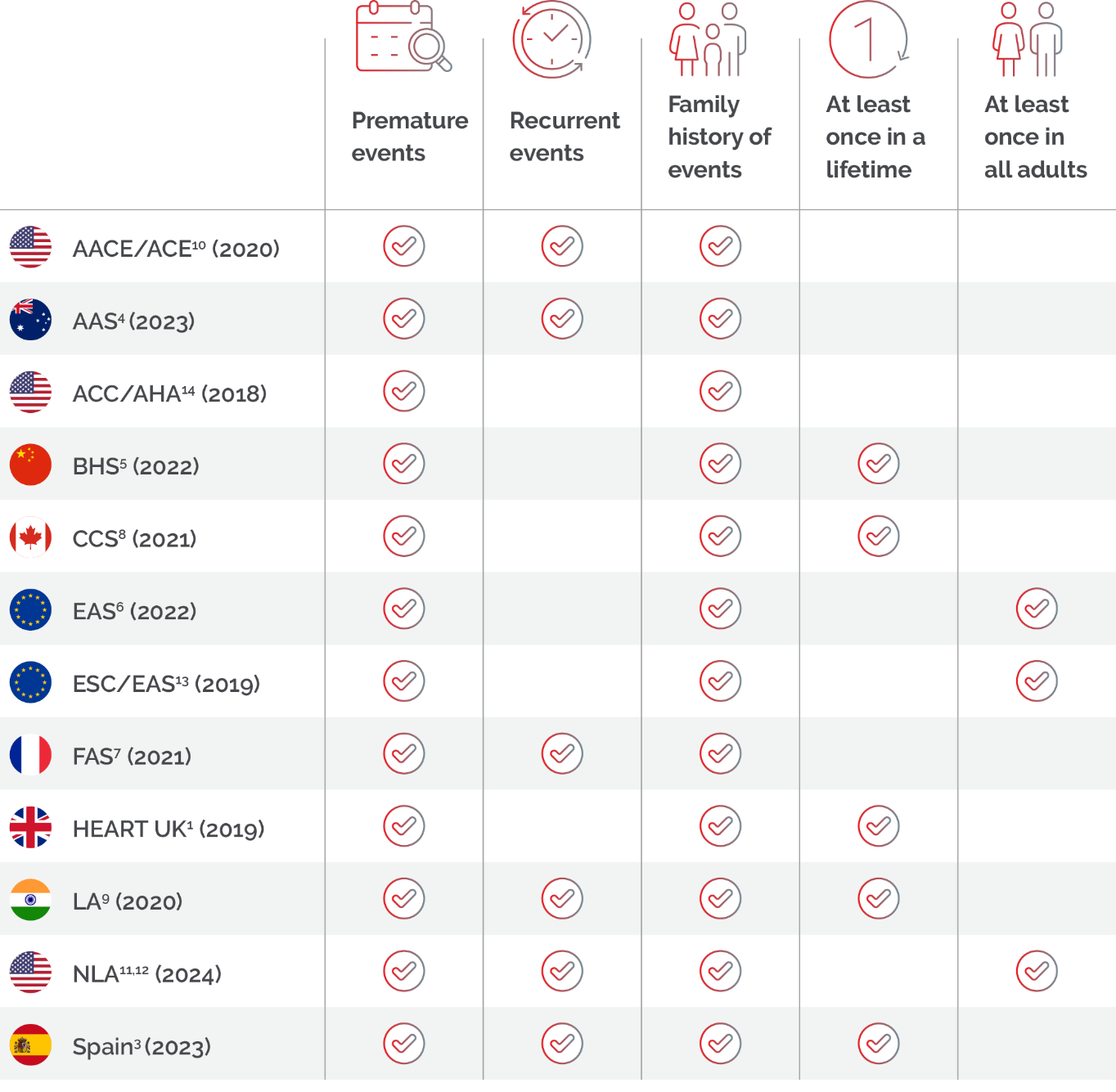

The measurement of Lp(a) levels is recommended by numerous national and international guidelines in patients with premature, recent, recurrent, and a family history of CV events; with some recommending Lp(a) testing at least once in all adults.

The National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke for the United Kingdom and Ireland also recommended Lp(a) testing in patients with ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack of presumed atherosclerotic cause below 60 years of age.

AAS, Australian Atherosclerosis Society; ACC, American College of Cardiology; AACE/ACE, American College of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology; AHA, American Heart Association; BHS, Beijing Heart Society; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; EAS, European Atherosclerosis Society; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; FAS, French Atherosclerosis Society; LAI, Lipid Association of India; NLA, National Lipid Association.

Testing considerations for accurate

diagnosis in certain populations

Testing in youth

In youth, Lp(a) measurement is recommended when there is a history of ischaemic stroke, or a parent has premature ASCVD and no other identifiable risk factors. Multiple testing may be required as Lp(a) levels may increase until adulthood.6 A Dutch study involving 2,740 children reported that mean Lp(a) levels increased from eight years of age, although this was less frequent in those who reached adulthood without lipid-lowering therapy than those subsequently treated with statins or ezetimibe (22% vs. 43%, respectively; 9% for those on ezetimibe).16

Pregnancy’s role in Lp(a) levels

Evidence in recent decades has shown that women have the same or even greater CV risk than men of the same age, attributed to female sex hormones. Different stages of a woman’s life can impact on Lp(a) levels, from newborn to menopause, including other critical moments such as menarche and pregnancy.17

Lp(a) levels are known to approximately double during pregnancy, but the underlying mechanisms remain partially understood. Theories suggest that oestrogen may affect Lp(a) synthesis and clearance, Lp(a) could function as an acute phase protein in response to endothelial damage, or it may play a role in placental development.17

Given these fluctuating Lp(a) levels throughout different life stages, it is crucial to consider when Lp(a) testing should be incorporated to better assess cardiovascular risk in women and guide appropriate management.

Kidney disease, liver disease and acute infections

The European Atherosclerosis Society advises that repeated Lp(a) measurements are generally not required, with the exception of kidney disease, liver disease and acute infections. Impaired kidney function may increase Lp(a) levels, potentially due to increased hepatic Lp(a) synthesis, peritoneal dialysate or impaired catabolism. As Lp(a) is produced in the liver, hepatic impairment may decrease levels. Additionally, acute infections can transiently alter Lp(a) levels, meaning re-testing may be warranted once the acute phase has resolved.6

Management of patients with elevated Lp(a)

Knowing the extent of Lp(a)-mediated risk can inform treatment intensification of global cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor management. Lp(a) testing can reveal a common underlying genetic cause of CVD risk, often explaining premature events or a family history of events. Patients knowing and understanding their Lp(a) status could inform positive behavioural change (e.g. motivation to adhere to treatments and lifestyle changes).

A role for formal family cascade testing for raised serum Lp(a) has not yet been established. However, given the dominant inheritance of Lp(a) levels, the testing of family members of index cases with severely raised levels (>200 nmol/L) may be useful. Genetic testing for single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with serum Lp(a) levels is not currently advocated in routine clinical practice.1

HEART UK’s consensus statement provides recommendations for managing patients, in both primary and secondary prevention, with Lp(a) levels >90 nmol/L.1 These recommendations include:

- reducing overall atherosclerotic risk

- controlling dyslipidaemia and

- consideration of lipoprotein apheresis as per the HEART UK Lipoprotein apheresis statement.

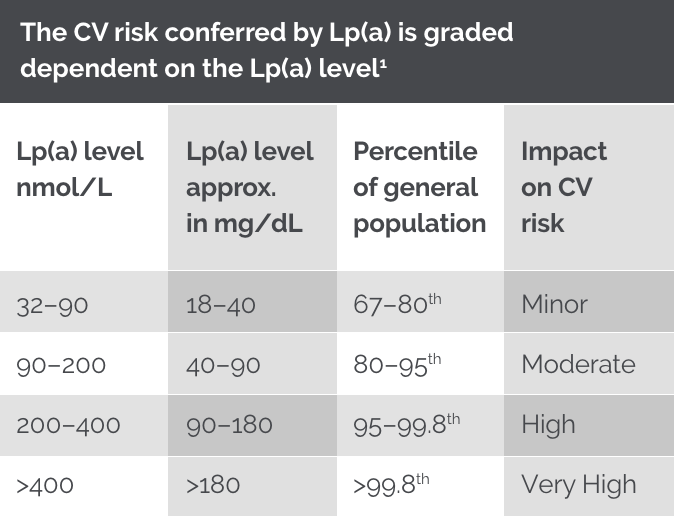

The factor to convert Lp(a) values from nanomoles per litre of apo(a) to milligrams per decilitre is for guidance only.

Lp(a) testing may benefit patients with CVD, in particular patients with recent, recurrent, and premature* CV events.6,9,11,14

*Consult local guidelines for the definition of premature. ACC/AHA 2018 guidelines: Family history of premature ASCVD (males aged <55 years; females aged <65 years); ESC/EAS 2019 guidelines: Family history of premature CVD (men aged <55 years; women aged <60 years).13,14

References:

- Cegla J, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2019. 291:62-70.

- Mehta A, et al. Atherosclerosis. 2022 May:349:42-52.

- Velilla TA, et al. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2023;43(4):474–483.

- Ward NC, et al. Heart Lung Circ. 2023;32(3):287–296.

- Li JJ, et al. JACC: Asia. 2022;2(6);653–665.

- Kronenberg F, et al. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3925–3946.

- Durlach V, et al. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;114:828–847.

- Pearson CG, et al. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021; 37:1129–1150.

- Puri R, et al. J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68(11[Special]):8–9.

- Handelsman Y, et al. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(10):1196–1224.

- Wilson DP, et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(3):374–392.

- Koschinsky et al. J Clin Lipidol. 2024; 000, 1-12.

- Mach F, et al. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111–188.

- Grundy SM, et al. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082–e1143.

- 2023 National Clinical Guideline for Stroke (For the UK and Ireland). https://www.strokeguideline.org/app/uploads/2023/04/National-Clinical-Guideline-for-Stroke-2023.pdf [Last accessed July 2025].

- de Boer LM, Hof MH, Wiegman A, Stroobants AK, Kastelein JJP, Hutten BA. Lipoprotein(a) levels from childhood to adulthood: data in nearly 3,000 children who visited a pediatric lipid clinic. Atherosclerosis 2022;349:227–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.03.004.

- Pablo Corral, et al., Lipoprotein(a) throughout life in women, American Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 20, 2024, 100885, ISSN 2666-6677, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2024.100885.

- Heart UK. Lipoprotein (a) disorder gets SNOMED codes. Available at: https://www.heartuk.org.uk/news/latest/post/188-lipoprotein-a-disorder-gets-snomedcodes [Accessed: July 2025]

UK | July 2025 | FA-11414811